Page 2

Quality Resource Guide –

Infection Control and OSHA Update Part One 3rd Edition

www.metdental.com

Guidelines and Regulations

I

t is important to realize that the Occupational

Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and

the Center for Disease Control (CDC) are two

completely different governmental agencies with

different mandates (Table 1). The CDC develops

guidelines designed to protect both the patient

and the HCW, while OSHA regulations apply only

to the latter. Guidelines published by the CDC or

other advisory agencies do not carry the weight

of law possessed by a regulatory agency such

as OSHA. OSHA has the authority to require and

enforce compliance with recommended infection

control practices and procedures. OSHA relies

upon appropriate authorities, including the CDC,

to provide background information when they

formulate their standards. It is important that

dental providers be aware of updates or changes

to recommended infection control practices to

provide the safest environment possible for their

patients and employees, as well as to remain in

compliance with OSHA regulations.

Governmental regulations from federal agencies

such as the OSHA, and state and local health

departments, require the HCW to be trained

in appropriate infection control practices and

other safety precautions. They also require

application of these measures during patient care

to reduce potential risks of disease transmission

to the patient and the HCW. The development

of a specific set of OSHA regulations to protect

the HCW from occupational risks associated

with bloodborne disease transmission began

in the 1980’s when unions representing HCWs

petitioned OSHA to require employers to have

a workplace free from recognized harm. More

specifically, unions wanted employers to protect

employees from occupational HBV infection. After

a series of public hearings, OSHA published the

Bloodborne Pathogens Standard on December

6, 1991.

3

These regulations were based on

CDC universal precautions recommendations

and went into effect in early 1992.

4

The OSHA

standard imposed obligations on employers to

provide safe and healthful work environments

for all HCWs. Requirements included work

practice controls, engineering controls, personal

protective equipment, and administrative controls.

In the dental setting these controls can be

described as:

1. work practice controls relating to the manner in

which a task is performed and advising the use

of safer work practices designed to minimize

the risk of disease transmission;

2. engineering controls that are technology-based

(refer to items or instruments that isolate a

hazard, such as a sharp’s disposal container);

3. personal protective equipment including the

use of gloves, masks, protective eyewear, and

protective clothing to prevent contamination

of the HCW during the delivery of dental care.

4. administrative

controls

(the

policies,

procedures and practices within a dental office

that reduce risks associated with bloodborne

disease transmission).

Revisions to the Bloodborne Pathogens Standard

were mandated in 2001.

5

These revisions clarified

the need for employers to consider safer needle

devices as they become available and to involve

employees directly responsible for patient care

(e.g., dentists, hygienists, and dental assistants)

in identifying and choosing such devices.

Engineering controls are available which can be

used as the primary method to reduce exposures

to bloodborne pathogens. The controls include

sharps containers, self-sheathing needles, safety

scalpels with retractable blades or covers, as

well as safer medical devices, such as sharps

with engineered sharps injury protection and

needleless systems. Dental anesthetic syringes

and needles that incorporate safety features have

been developed for dental procedures, and their

implementation and routine use in dental facilities

is increasing.

Standard Precautions

I

nfection control recommendations for

dentistry have routinely focused on the use of

universal precautions (UP). These precautions

were designed to prevent the transmission of

HBV, HIV, HCV and other bloodborne pathogens

during treatment procedures. While the adoption

and routine use of UP proved to be very successful

in minimizing the potential for transmission

of bloodborne pathogens, these practices did

not eliminate the need to address disease-

specific isolation precautions for non-bloodborne

infections in outpatient settings.

A body substance isolation system (BSI) was

proposed in 1987

6

that focused on the reduction

of transmission of infectious materials from any

moist body substances. The BSI was designed

to address isolation procedures of all moist,

potentially infectious body substances regardless

of their presumed infectious status. The BSI

system protocol advocated additional protection

for the HCW, including immunization against

selected infectious diseases transmitted by

airborne or droplet modalities (measles, mumps,

rubella, varicella) and the use of appropriate

barriers (protective clothing).

CDC developed and published new guidelines

for isolation precautions in hospitals in 1996

7

,

in an effort to prevent any potential infectious

problems that might arise as a result of the

confusion between BSI and UP. The 1996

guidelines incorporated the major features

of UP and BSI. Since that time, the use of

Standard Precautions has replaced the use of

both of its individual components. Standard

Precautions apply to contact with blood, body

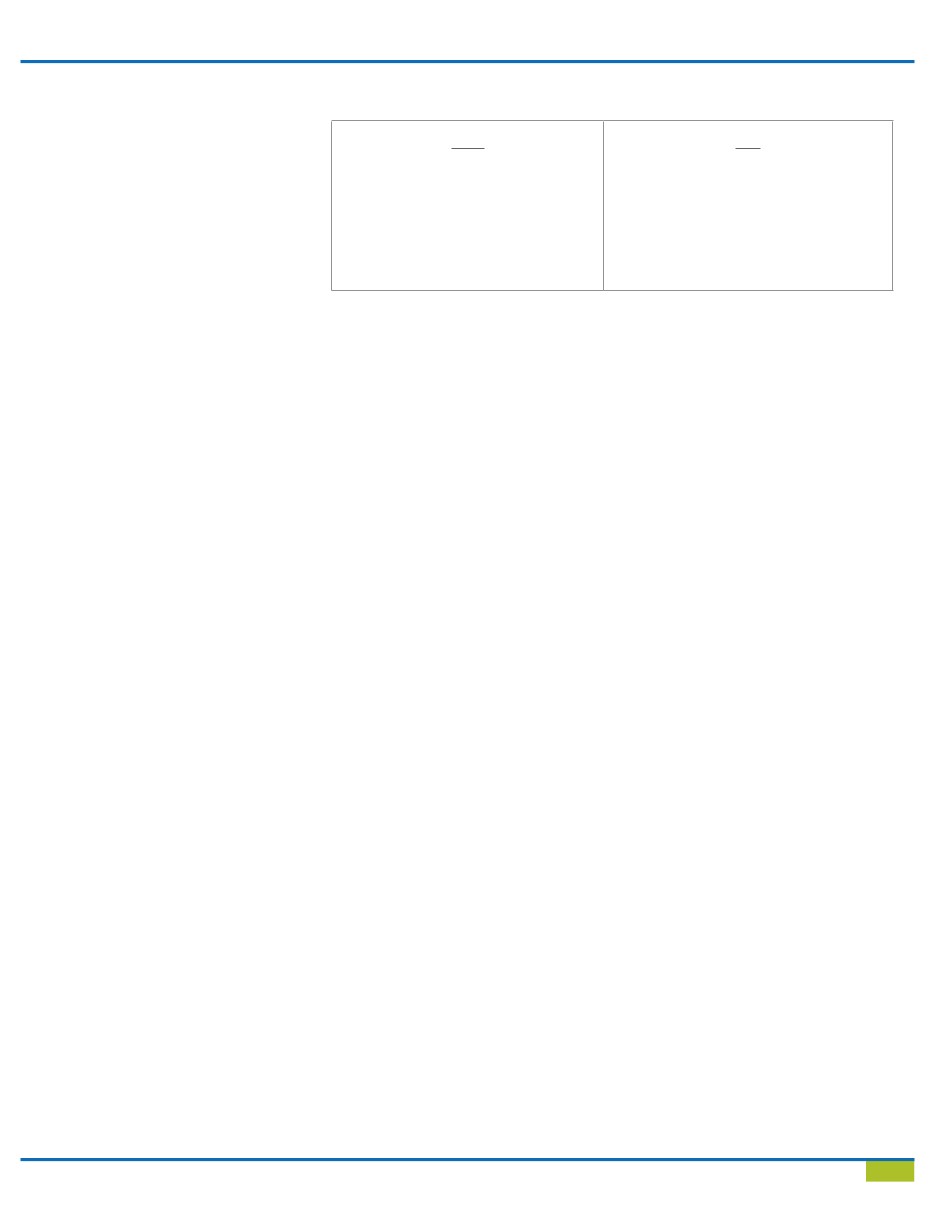

Table 1 - OSHA Regulations vs. CDC Recommendations

OSHA

•

Regulatory agency

•

Set and enforce standards

•

Investigates and inspects

•

Blood-borne Pathogen Standard

29 CFR 1910.1030 and CPL 2-2.69

•

Employee protection

CDC

•

Non-regulatory agency

•

Guidelines/Recommendations

•

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

Recommendations and Reports

•

Often enforced by state