|

Acute Gingival Conditions

Gingivitis

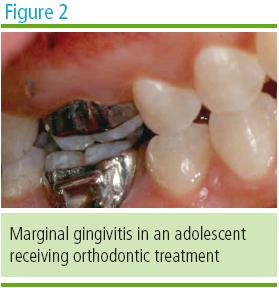

The development and rate of progression of gingivitis have been shown to be

age-dependent based on factors such as sex hormone changes that affect

host-parasite interactions, increased blood vessel permeability, exaggerated

responses to microorganisms, and lack of attention to proper oral hygiene

(Figure 2). Primary preventive strategies should be initiated to intercept

the process of reversible adolescent periodontal diseases; thereby, avoiding

the necessity to treat irreversible periodontal diseases in adulthood.

Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis

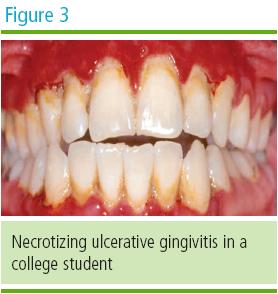

Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis first appears most frequently during the

circumpubertal years. A stress-related component and an altered

host-resistance are associated with this condition (Figure 3). Causative

bacteria include Borelia vincentii and Prevotella intermedia. Clinically,

interproximal gingival necrosis is accompanied by rapid onset of gingival

pain. Treatment includes professional debridement of local irritants with

prophylaxis and scaling accompanied by meticulous personal home care using a

soft-bristled toothbrush. Therapeutic mouthrinses such as 0.2% chlorhexidine

gluconate solution can be recommended and in the presence of systemic

conditions, e.g. fever and adenopathy, antibiotics such as penicillin or

metronidazole can be prescribed. The presence of oral malodor associated

with necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis is yet another opportunity for the

dental team to promote a comprehensive oral health home care regimen.

Herpes Simplex

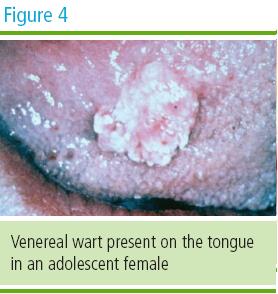

Adolescents who have not been exposed to the herpes simplex virus (HSV) can

be affected with a primary infection. Teenagers who engage in oral sex may

present with soft tissue lesions related to sexually transmitted diseases

and HSV-2 lesions in the oral cavity and perioral regions (Figure 4).

Questions related to the adolescent patientís sexual activity are advisable

in the presence of HSV lesions. While there is no known cure for HSV,

treatment for this condition is palliative. Antiviral medications such as

acyclovir along with analgesics such as acetaminophen can be prescribed to

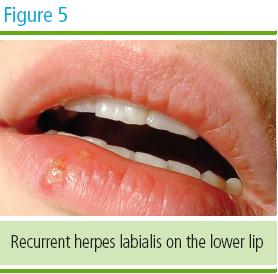

alleviate symptoms for the adolescent patient. Recurrent episodes of herpes

labialis (RHL) may be treated with pencyclovir cream for perioral lesions

(Figure 5).

Third Molars

The extraction of impacted third molars is an anticipated event by many

adolescents. Third molars usually emerge between the ages of 17 and 25

years. During the process of eruption, the development of pericoronitis is a

common, pain-causing sequela. Periodontal therapy in this region should

focus on eliminating pathogenic bacteria.

Periodontal

disease around asymptomatic third molars may progress even in the absence of

symptoms. This should prompt dentists to monitor the eruption of third

molars in adolescent patients. Periodontal disease is indicated by probing

depths > 4 mm around these teeth. Further anaerobic bacterial infection may

spread from the supporting tissues surrounding the third molars to other

teeth, particularly the second molars. This may result in the disruption of

the periodontal ligament, root resorption, and pocket depth associated with

loss of attachment. These factors should alert the dentist to thoroughly

evaluate the third molars in adolescent patients to identify and prevent the

onset of periodontal disease.10 Despite local lavage and the administration

of systemic antibiotics and analgesics, if the periodontal pockets and/or

symptoms persist extraction of the third molars may be the most prudent

long-term solution.

Another

consideration is the evaluation of third molars in adolescent female

patients who are pregnant. Periodontal pocketing around third molars has

been linked to a higher incidence of premature births. Not only should

dentists evaluate periodontal pockets surrounding the third molars of their

pregnant female adolescent patients, but all women of childbearing age for

systemic risks from oral inflammation associated with periodontal

pathology.11 In addition, research suggests that women of childbearing age

who take oral contraceptives may have a higher incidence of post-third molar

extraction dry socket (localized osteitis).12 For further information on

womenís oral health, the reader is referred to the MetLife Quality Resource

Guide entitled Womenís Oral Health Concerns, 2nd Edition.

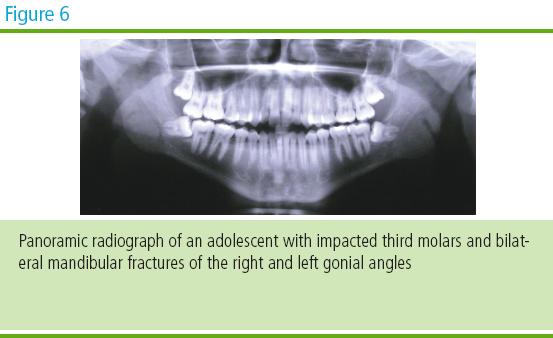

Impacted third

molars may pose an additional concern. For example, the presence of impacted

third molars or their extraction make the gonial angle of the mandible more

susceptible to fracture in adolescent athletes (Figure 6).

|